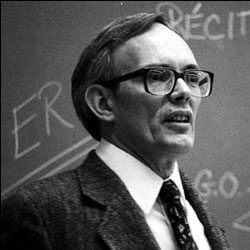

Charles Fisk

Charles Brenton Fisk (1925-1983) was the first American organbuilder to build significant tracker organs in the 20th century.

His study of early American and European instruments led him to return to mechanical action, and to set a new course for American organbuilding. He modeled his shop on collaborative enterprise, launching the careers of four other North American organbuilders and providing the foundation for those who carry on the company he founded. Nearly a third of present day shop members worked with Charlie before his death, and continue to be inspired by his approach to study, problem solving, and collegial respect.

C. B. Fisk Inc. was founded in 1961 by Charles Brenton Fisk. Born in Washington, DC and reared in Cambridge, Massachusetts, he had a passion for music and grew up tinkering with hi-fi equipment. As a youth he was a chorister at Christ Church on Cambridge Common and sang under Choirmaster E. Power Biggs; he also played the trumpet and the organ. With plans for a career in nuclear physics Charles began studying at Harvard University, but WWII intervened and Charles enlisted in the army. Soon after, at the age of 19, he began working under Robert Oppenheimer at Los Alamos as a minor technician on the detonator team for the Manhattan Project. After the war he resumed his studies at Harvard and after graduation continued at Stanford University.

During his first semester at Stanford, he decided to redirect his energies to organbuilding, first apprenticing himself with John Swinford in Redwood City, California, and then in Cleveland, Ohio, with Walter Holtkamp, Sr., who was at the time the most avant garde of American organbuilders. Charles went on to become a partner and later sole owner of the Andover Organ Company. In 1961 he established C. B. Fisk near his childhood summer home on Cape Ann, Massachusetts.

Charles Fisk

Writing

Memorials

- Barbara Owen

- Brian Jones

- Charles Nazarian

- Daniel Pinkham

- David Fuller

- David Klepper

- David M. Waddell

- Fritz Noack

- George Kent

- George Taylor

- Greg Bover

- J. Melvin Butler

- John Ferris

- John S. Mueller

- Jonathan Ambrosino

- Josephine Singer

- Margaret "Meg" Flowers

- Margie Singer

- Miranda Fisk

- Morgan Faulds Pike

- Owen Jander

- Peter Hewitt

- Peter Sykes

- Quentin Regestein, M. D.

- Richard Bamforth

- Robert Anderson

- Robert Cornell

- Roger Martin

- Stephen Roberts

- Steve Bartlett

- Steven Dieck

- Tom and Carol Foster

- Tomoko Akatsu Miyamoto

- Walter Holtkamp, Jr.

- William Dowd

- William Smith

- Yuko Hayashi

THE ORGAN IS…A MACHINE, whose machine-made sounds will always be without interest unless they can appear to be coming from a living organism. The organ has to seem to be alive.

THE ORGAN IS…A MACHINE, whose machine-made sounds will always be without interest unless they can appear to be coming from a living organism. The organ has to seem to be alive.— Charles Fisk, The Organ’s Breath of Life

The workshop attracted bright young co-workers who combined their talents in music, art, engineering, and cabinet making to build organs that redefined modern American organbuilding. Always experimenting, Charles Fisk was one of the first modern American organbuilder to abandon the electro-pneumatic action of the early twentieth century and return to the mechanical (tracker) key and stop action of European and American instruments of an earlier time. In 1967 at Harvard University and again in 1979 at House of Hope Church in St. Paul, Minnesota, Fisk constructed what were, at the time of their building, the largest four-manual mechanical action instruments built in America in the 20th century.

The company has also built a number of instruments based on historical organs, among them one at Wellesley College, patterned after North German organs of the early 17th century, one at the University of Michigan in the manner of the 18th century Saxon builder, Gottfried Silbermann, and three-manual instruments at Rice University and Oberlin College modeled on the work of the 19th century French master builder Aristide Cavaillé-Coll. The large four-manual dual-temperament instrument at Stanford University used modern technology to combine different aspects of historical organ styles. Concert hall organs at the Meyerson Symphony Center in Dallas, Minato Mirai Hall in Yokohama, Benaroya Hall in Seattle, and Segerstrom Hall in Costa Mesa, were designed for maximum impact with orchestra as well as for solo repertoire. In 2003 C. B. Fisk built a five-manual organ for the Cathedral in Lausanne, Switzerland, the first American organ to be made for a European cathedral, and in 2010 installed their first instrument in South Korea. In 2012 Opus 139 was completed in the rear gallery of Memorial Church, Harvard University, replacing Opus 46, Charles’s landmark instrument of 1967.

C. B. Fisk still combines the science of physics and the art of music as practiced by Charles Fisk, who saw himself as a teacher and tirelessly shared his insight and experience with others. His style of leadership, modeled after the team of scientists he worked with at Los Alamos, involved his co-workers in the day-to-day decisions about the concepts and construction of the instruments. The same people who were drawn by Charles Fisk’s bold ideas carry on his work and share their insight and experience with another generation of organbuilders. This dedicated community continues to use its talent and imagination to stretch the boundaries of organbuilding, producing instruments that add to the rich heritage of the King of Instruments.